Getting Started with Land Acknowledgements

NOTES ON LANGUAGE: A variety of language is used to describe the people who first inhabited the North American continent before colonizers arrived in the 15th century, continuing through the annexation of Hawai’i in 1898. What vocabulary we use depends on whether we are quoting someone else’s language, talking about legal matters, statistics, or data tracked by the U.S. government, or referring to cultural identity. Read more about our use of language and see our land acknowledgment.

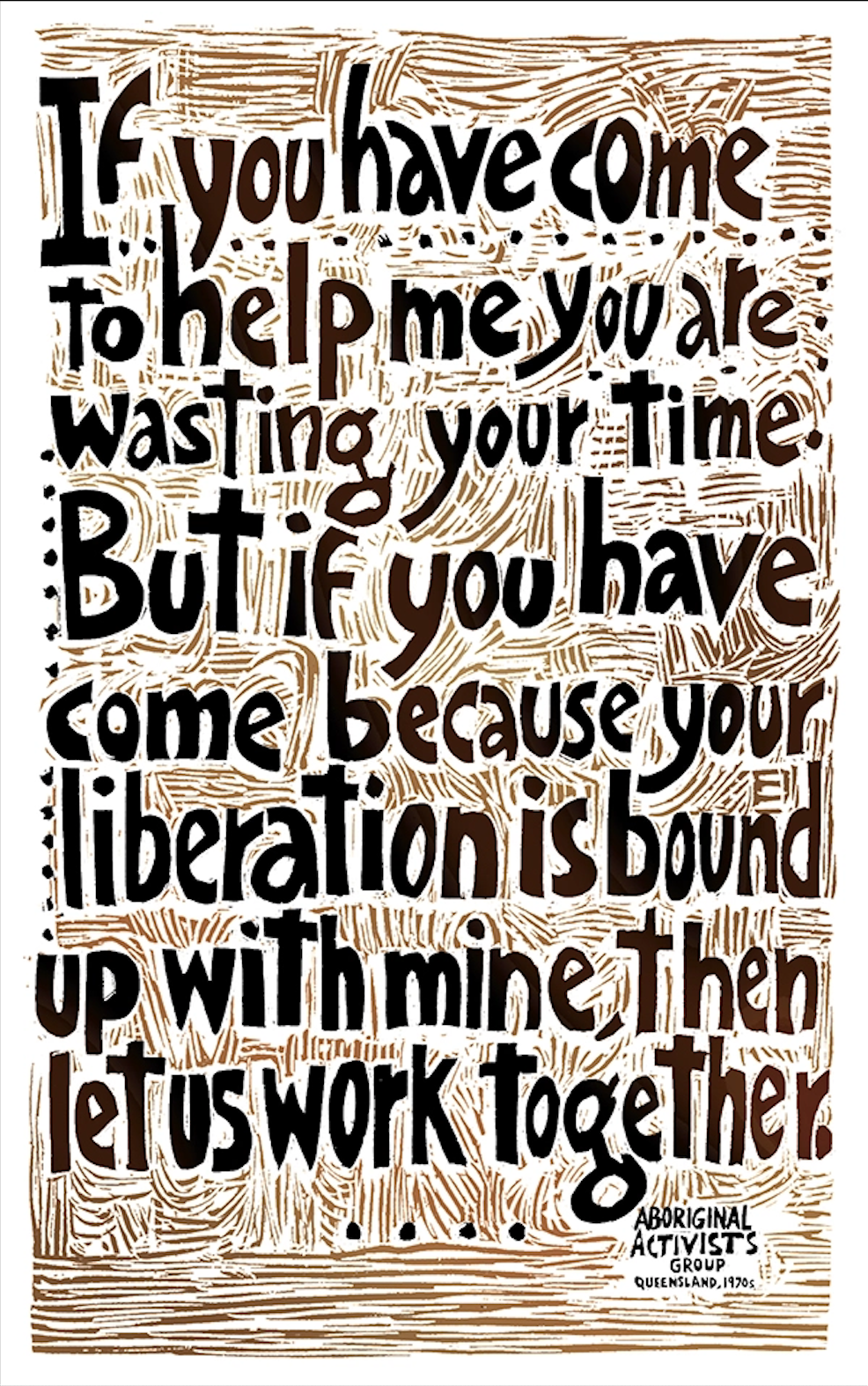

There is a quote that is always with me: “If you have come to help me you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” This is from an Aboriginal Activists Group that met in 1970 in Queensland, Australia.

There is a quote that is always with me: “If you have come to help me you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” This is from an Aboriginal Activists Group that met in 1970 in Queensland, Australia.

Land acknowledgements, like sharing our gender pronouns, are another part of bringing our fuller selves to our work and fostering an inclusive meeting culture. Land acknowledgements can demonstrate a respect for the original stewards of the land where we reside and gather. They can be an important tool for Natives and non-Natives to facilitate both honoring the past and acknowledging its impact on the present and future. Factors like where you live and if other equity practices (i.e. land acknowledgements and pronoun sharing) are incorporated into the other parts of your life can affect how fluidly you bring them into your professional role. By practicing inclusive meeting culture, humbly and with good intention, we have an opportunity to positively impact our participants and the communities we serve.

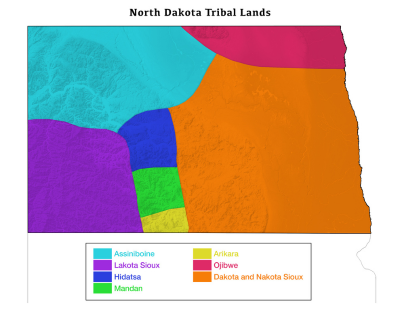

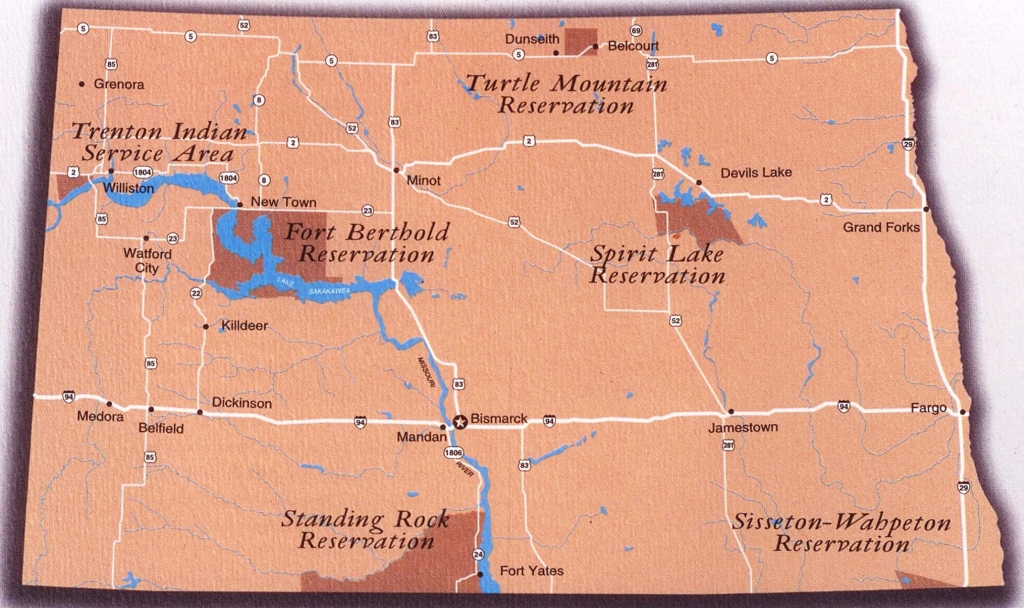

Our campus featured the film Waterbuster by Carlos Peinado, whose mother and family were impacted by this forced buyout of some of the most fertile cropland and homeland in the state. The film is available to watch online – I encourage you to watch and learn. Despite years of systemic marginalization, tribal communities in North Dakota are preserving their cultures and are an important source of leadership and environmental activism in the face of oil and gas development.

The full story of how we came to occupy these lands must be told, and land acknowledgements are a place to start. That said, it’s also important to understand that a range of perceptions of land acknowledgements exists among Native people themselves. As the landing page for the National Museum of the American Indian describes:

After millennia of Native history, and centuries of displacement and dispossession, acknowledging original Indigenous inhabitants is complex. Many places in the Americas have been home to different Native Nations over time, and many Indigenous people no longer live on lands to which they have ancestral ties. Even so, Native Nations, communities, families, and individuals today sustain their sense of belonging to ancestral homelands and protect these connections through Indigenous languages, oral traditions, ceremonies, and other forms of cultural expression.

Why do Land Acknowledgements?

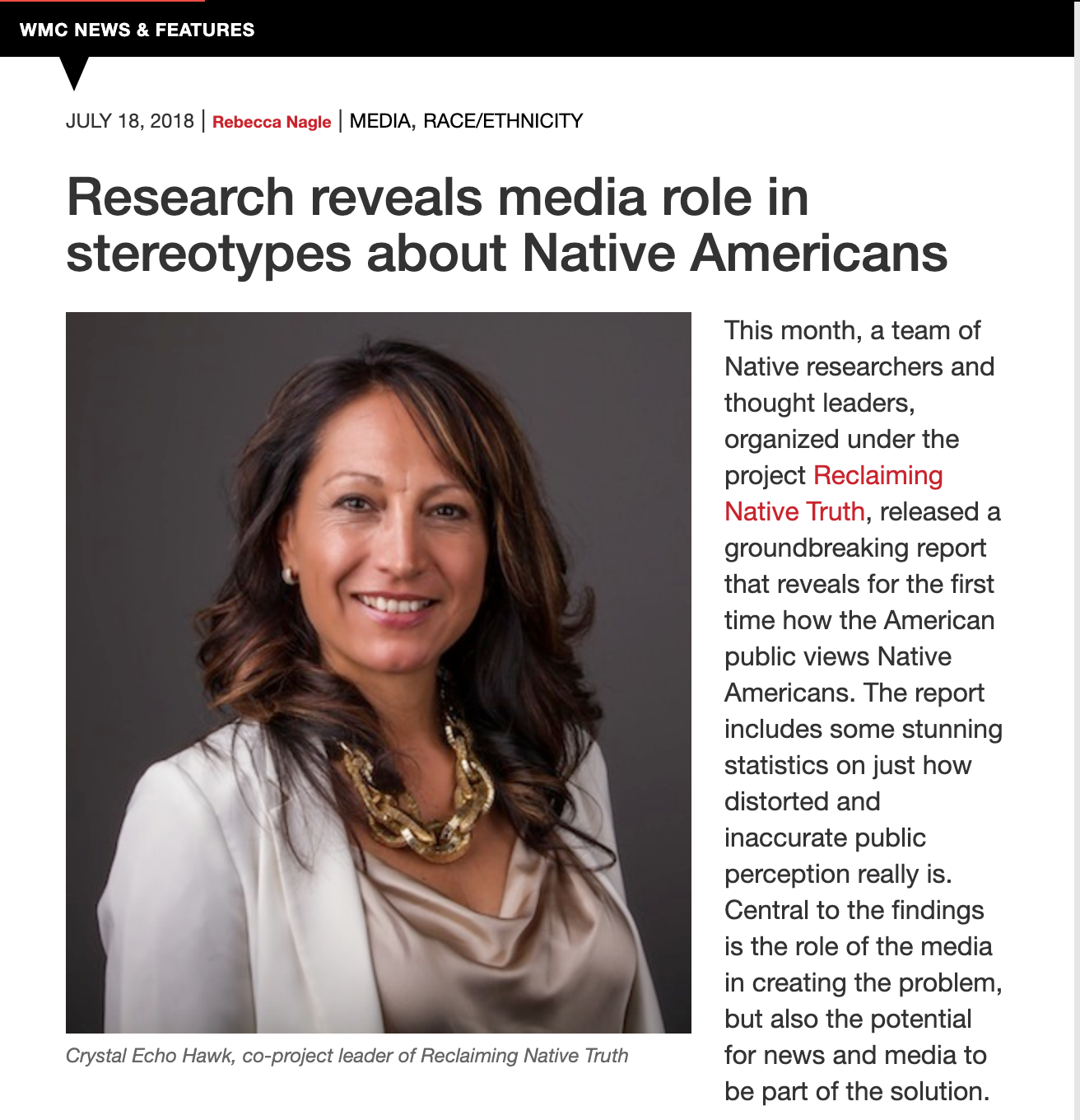

As referenced in a NICHQ insight earlier this year, research has shown that stereotypes and a lack of representation perpetuate invisibility, erasure, and marginalization, which contribute to disparate health outcomes.

As referenced in a NICHQ insight earlier this year, research has shown that stereotypes and a lack of representation perpetuate invisibility, erasure, and marginalization, which contribute to disparate health outcomes.

Crystal Echo Hawk is co- project leader of Reclaiming Native Truth, which in 2018 released a report that detailed how representation of contemporary Native Americans was found to be almost completely absent from K-12 education, pop culture, news media, and politics. Two-thirds of respondents said they don’t know a single Native person. Only 13 percent of state history curriculum standards about Native Americans cover events after the year 1900.

Staying Authentic and Accountable

As we each navigate our own understanding of equity, it can be challenging to avoid being performative – to say or do what “should” be said or done without knowing why or toward what greater purpose. To avoid the harm that performative language may cause, non-Natives each need to find an authentic way to incorporate equity-focused, inclusive practices that are becoming (or should become) a standard part of our introductions and convening of intentional spaces, both virtual and in-person.

Ask yourself: How might incorporating land acknowledgements help create collaborative, accountable, and continuous relationships with the original inhabitants of the land?

It’s important that we don’t start (or stop) with land acknowledgements – building relationships, showing up, and driving action to support tribal communities is an ongoing process. Cutcha Risling Baldy, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe and an associate professor of Native American Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, asks helpful critical questions in a recent NPR article about land acknowledgements:

“Now it’s time to think about what that actually means for you or your institution. What are the concrete actions you’re gonna take? What are the ways you’re gonna assist Indigenous peoples in uplifting and upholding their sovereignty and self-determination?”

“Now it’s time to think about what that actually means for you or your institution. What are the concrete actions you’re gonna take? What are the ways you’re gonna assist Indigenous peoples in uplifting and upholding their sovereignty and self-determination?”

The article also details how Risling Baldy modeled how to connect a land acknowledgement to positive action at a lecture in November 2022 by pausing, putting up a QR code, and asking audience members to support a nearby indigenous community garden project. Fawn Pochel, who identifies as First Nations Ojibwe, said her group received more than $200 in unexpected donations with in 24 hours.

How Organizations Can Incorporate Land Acknowledgements

1. Start with learning – on your own and with others in your organization.

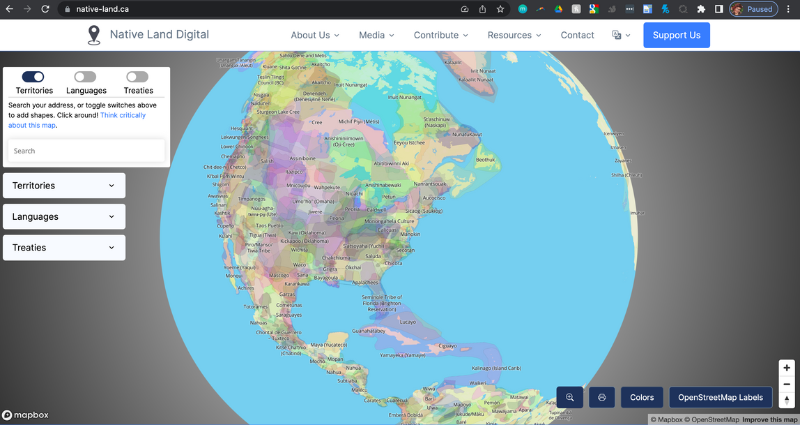

In addition to knowing about the impact of colonialism on a national level, it’s imperative you become acquainted with local tribes where you live and work – whether they still reside there or if they consider where you live part of their ancestral homeland. You can learn so much by researching on your own, but we recommend a comprehensive application called NativeLand, created by Native Land Digital, whose mission is to foster conversations about the history of colonialism and settler-Indigenous relations. This beautiful tool works on desktop or via a mobile app you can use even while offline – simply zoom into the lands where you reside or enter an address. Informational territory landing pages link to external sites and resources so you can continue your learning. Once you know the names of the original stewards of the land on which you live and/or work, learn how to say them, and facilitate discussions about what you and others learn.

2. Decide where and when you will incorporate land acknowledgements.

This is also something you can enhance over time – again, being authentic is important. One of the easiest places to normalize land acknowledgements is by including them in standard introductions for meetings and other similar spaces.

It can be simple, but what’s important is that it’s there, with informed intention. Organizations can also create signs in their offices and landing pages on their websites to publicly commit and share their understanding of the historical and present-day Indigenous community where they live. Once your organization gets comfortable, you could consider more thorough acknowledgements ahead of larger events.

3. Keep going. What’s next – for you, for your organization, for the work?

Maintain momentum and keep Risling Baldy’s words in mind – What are the concrete actions from here that are welcomed? Take action beyond the acknowledgment and establish authentic, meaningful relationships with local or regional tribal communities so you can understand how they want to be supported – and compensate them for their time. Understand the nuances between offering help vs. shared liberation. Within the organization, create space to have ongoing and meaningful conversations about how teams can integrate land acknowledgements and what additional ideas can be offered to indigenous communities.