Race and the Inequity in Maternal and Infant Health

The United States falls far behind other industrialized nations in the most basic pulse check of a nation’s health – infant mortality. While many valid reasons exist to illustrate why we have worse outcomes compared to other nations, a single truth is evident but rarely acknowledged. That is, if we are serious about effecting a widespread change in birth outcomes we must acknowledge how historical racism impacts the health of all community members in particular people of color. To address staggering inequities in birth outcomes between non-Hispanic black babies and non-Hispanic white babies, it is necessary for public health practitioners and healthcare providers to take ownership for how structural racism affects specific communities.

First, having a working definition for structural and institutionalized racism is a critical step for practitioners working to reduce disparities. There is already a framework by which practitioners can begin to understand institutionalized racism as the policies, regulations, and expectations in society that prevent equity in housing, education, health, or civic liberties. A black woman in the United States has a very different experience of her race comparatively to women in other nations because of our history of slavery, civil disenfranchisement and reluctance to address systemic barriers caused by racism. Because institutionalized racism never explicitly mentioning race, policies and regulations have disproportional negative outcomes among communities of color, exacerbating the social determinants of health that initiatives like Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network to Reduce Infant Mortality (Infant Mortality CoIIN) seek to address.

Due to an accumulation of stress over their lifetime from institutional, personally mediated and internalized racism, women of color are entering pregnancy at higher risk of complications than their white counterparts. Allostatic stress is internalized from the everyday micro and macro aggressions experienced by black women in the United States. Life Course theory posits that this type of stress physically manifests in a woman’s body and can have a negative impact on her future children’s health as well as her own.

Disparities Between Communities

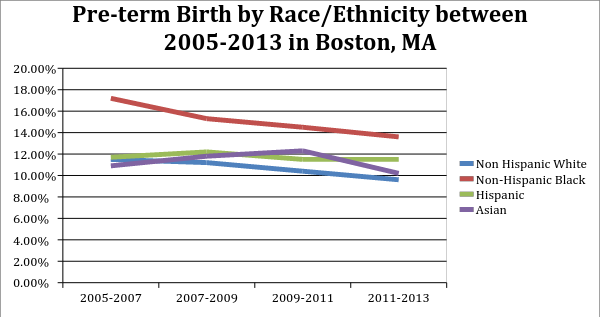

Data on preterm birth among black infants indicates that there is a clear inequity. Preterm birth is defined as being born at less than 37 weeks into the gestational period, likewise a full-term birth is considered to be equal or more than 37 weeks of gestation.

As an example, the preterm birth rate was 8.6 percent of all babies born in Massachusetts as of 2013. Boston itself reveals some stark disparities of birth outcomes across races. While there have been steady declines in the prevalence of preterm births for all races, non-Hispanic black infants still have the highest prevalence of preterm births according to 2013 data. The largest preterm birth inequity exists between non-Hispanic black infants, ranging from 17.2 percent 13.6 percent of all live births between 2005 and 2013 and 11.5 percent to 9.6 percent for non-Hispanic white infants during the same period.

Black babies, are at much higher risk of experiencing these negative implications due to their mothers increased exposure to toxic stress from institutionalized racism. Indeed, this trend of preterm birth and low birth weight among infants born to black mothers born in the United States is directly connected to a mother’s experience of racism, even when controlling for socioeconomic status and education levels between white mothers and black immigrant mothers.

Dire health consequences associated with being born preterm or low birth weight include increased risk for acute lung diseases, chronic diseases and mortality. Given the long-term health issues associated with preterm birth and low birth weight, some health professionals and public health practitioners are working to underscore racism as a determinant of health among black women in addressing disparities in birth outcomes. In acknowledging this duty to address systemic racism, health practitioners must reconsider how we reach target populations that are at higher risk of delivering preterm. Actions must include building trust in communities of color where there is a history of medical and public health abuses, advocating for a workforce that is representative of the communities being served and treating underserved communities as the experts of their own lived experiences in guiding how healthcare is practiced.

Avery Desrosiers is a second year Masters Candidate at Boston University School of Public Health. She is currently working as the HRSA/MCHB Grant sponsored MCH Practice Fellow at NICHQ.