Children and Their Families Have a Right to Gender-Affirming Healthcare

The story of kids like Shay is more common than you may realize – but not all turn out so positively. As more and more youth live their gender identity openly to achieve their optimal health, many of them experience discrimination, stigma, restricted access to medical care and mental healthcare, and increasingly, legislation on their bodily autonomy. In 2022 alone, more than 335 pieces of legislation aimed at controlling the existence of gender-diverse children and adolescents were introduced in state legislatures. And in July, 10 anti-LGBTQI+ laws went into effect, all education-related and ranging from banning classroom discussions of gender and sexuality to restrictions on sports teams that transgender students can join and restrictions on the bathrooms, lockers, and other facilities that transgender student can use. Experts say these laws could have a devastating impact on the mental health of LGBTQ students and create a culture of fear and suspicion among students and school staff. A poll from The Trevor Project, an LGBTQI+ suicide prevention support service, showed that 85% of transgender and nonbinary youth and 66% of all LGBTQI+ youth said that recent debates around anti-trans bills have negatively impacted their mental health.

How many youth are LGBTQ+?

Older estimates of the LGBTQI+ population at ~2% reflects the amount of stigma that older LGBTQI+ people experienced, keeping them from living open lives and achieving their optimal health. The same is not true for Generation Z, the biggest and most socially progressive generation of the bunch – more than 20% of Gen Z said they identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, according to a recent Gallup Poll. For context, this is nearly double the proportion of Millennials identifying as LGBT, and close to five times the number of Gen X who say they are LGBT. Just 2.6% of Baby Boomers identify as LGBT.

Health Disparities for LGBTQI+ Youth

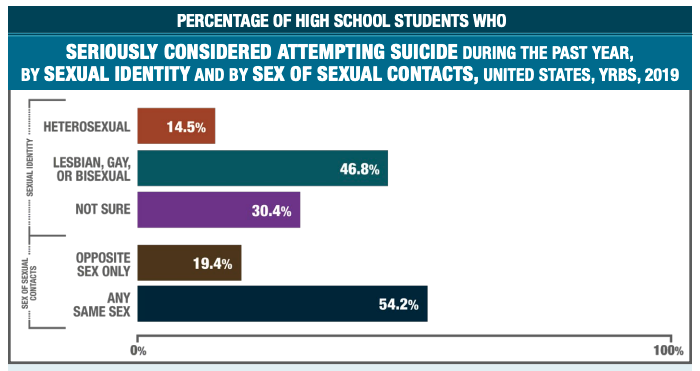

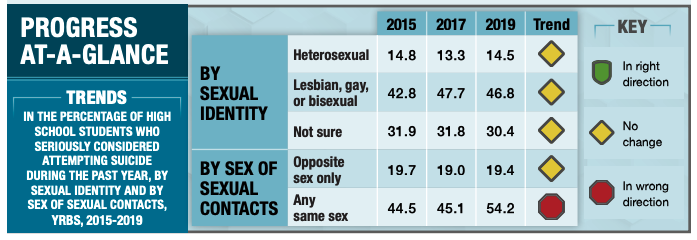

These factors, combined with a lack of support from family and bullying from peers, are why we are losing more LGBTQI+ youth to suicide than ever before, and anti-LGBTQI+ violence is on the rise. In the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Survey Summary Trends Report 2009-2019, a survey fielded to U.S. students, it was noted that sexual minority youth (SMY) are at increased risk for negative health and life outcomes – not from being LBGTQI+ but from the significant health disparities caused by bias, stigma, and discrimination. CDC research has found that compared to their peers, SMY have a higher risk of suicide, depression, substance use disorder, and poor academic performance. In 2019, SMY youth were nearly three times as likely to have “seriously considered attempting suicide” during the past year compared to their straight peers (Fig. 1).

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in its policy statement Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents, more gender-diverse youth and their families are presenting to pediatric providers for education, care, and referrals as a traditionally underserved population that faces numerous health disparities. The AAP acknowledges that the need for more formal training, standardized treatment, and research on safety and medical outcomes often leaves providers feeling ill-equipped to support and care for gender-diverse patients and their families.

What Care Providers Can Do

1. Familiarize yourself with best practices and modern models of care.

The positive part of this situation is that there’s no shortage of guidance on how to support gender-diverse youth and improve health outcomes. There are a lot of myths and misconceptions about what constitutes gender-affirming care, and we agree with the AAP that the decision of whether and when to initiate gender-affirmitive treatment is personal and involves careful consideration of risks, benefits, and other factors unique to each family. It’s important to know and promote truths about gender-affirmitive care, for example, how puberty blockers are among safe, effective, and reversible methods to support gender-diverse youth.

How many youth are transgender?

According to the AAP, questions related to gender identity are rarely asked in population-based surveys, which makes it difficult to assess the size and characteristics of the population who is transgender or gender-diverse. According to the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, recent data from both the YRBSS and the CDC’s Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) create an opportunity to update prior populations of how many youth ages 13-17 identify as transgender in the U.S. Since 2017, only 15 states have elected to include optional questions on gender identity in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Survey of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is potentially still an underestimate given the stigma regarding those who openly identify as transgender and the difficulty in defining “transgender” in a way that is inclusive of all gender-diverse identities.

Using data from the 2017 and 2019 YRBSS and the 2017-2020 BRFSS, the Williams Institute found that among youth ages 13 to 17 in the U.S., 1.4% (about 300,000 youth) identify as transgender. This is about double previous estimates. Research also showed that transgender individuals are younger on average than the U.S. population. They found that youth ages 13 to 17 are significantly more likely to identify as transgender (1.4%) than adults ages 65 or older (0.3%).

In a gender-affirmative care model (GACM) endorsed by the AAP, pediatric providers offer care that is developmentally appropriate and oriented toward appreciating and understanding the youth’s experience of gender. Exploration of complicated emotions and gender-diverse expressions can be facilitated by a strong, nonjudgmental partnership with youth and their families, all while allowing questions and concerns to surface in a supportive environment.

The GACM works best when resources are integrated – medical, mental health, and social services, including specific supports for parents and families. Working together, providers help destigmatize gender variance, promote the child’s self-worth, facilitate access to care, educate families, and advocate for safer community spaces where children are free to develop and explore their gender.

In a GACM, providers work to convey the following messages:

- transgender identities and diverse gender expressions do not constitute a mental disorder

- variations in gender identity and expression are normal aspects of human diversity, and binary definitions of gender do not always reflect emerging gender identities

- gender identity evolves as an interplay of biology, development, socialization, and culture

- if a mental health issue exists, it most often stems from stigma and negative experiences rather than being intrinsic to the child.

Models for gender-affirmative care suggest that clinical assessment be conducted on an ongoing basis in the setting of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach, including the pediatric provider, a mental health provider ideally with experience caring for gender-diverse youth, a pediatric endocrinologist or adolescent-medicine gender specialist as available, and social and legal supports. Every gender-diverse youth’s experience is different, and there is no prescribed path.

2. Improve your data collection and reporting.

Pediatricians and other health professionals are in a unique position to routinely inquire about gender development in children and adolescents as part of recommended well-child visits and to be a reliable source of validation and support – sometimes they are the first to know there is some distress related to a gender-diverse identity. Care providers are also in an incredibly powerful position to ask information and collect data in a way that demonstrates an understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity. A policy brief from the Fenway Institute details some best practices for clinical settings – it primarily comes down to establishing trust through demonstration of understanding concepts of sexual orientation and gender identity, and creating opportunities for disclosure, as well as being clear about how medical information will be used.

3. Join families and other health professionals in creating inclusive environments.

We know from the Healthy People 2030 goals that social determinants affecting the health of LGBTQI+ people largely relate to oppression and discrimination, including legal discrimination in access to health insurance, employment, housing, marriage, adoption, and retirement benefits; lack of laws protecting against bullying in schools; lack of social programs targeted to and/or appropriate for LGBT youth, adults, and elders; and a shortage of healthcare providers who are knowledgeable and culturally competent in LGBTQI+ health.

The physical environment we need to co-create with and for LGBTQI+ youth includes safe schools, neighborhoods, and housing; access to recreational facilities and activities; availability of safe meeting places; and access to health services where they will be treated respectfully.

The social environment we need to co-create is one where everyone’s experience of their gender identity and gender expression is affirmed, supported, and celebrated. Adolescents who identify as transgender and endorse at least one supportive person in their life report significantly less distress than those who only experience rejection. In communities with high levels of support, it was found that nonsupportive families tended to increase their support over time, leading to dramatic improvement in mental health outcomes among their children who identified as transgender.

As physicians, public health professionals, and care providers, we have an obligation to support youth with unique healthcare needs who are at higher risk for negative health outcomes from discrimination, including bullying, physical assault, and suicide. Join us by engaging in meaningful dialogue about best practices for gender-diverse kids to improve quality of life, reduce mental health disparities, and most importantly, help the most historically marginalized kids achieve their optimal health.