Quality Improvement: A Necessary Addition to the Maternal and Child Health Tool Belt

As a current graduate student studying Public Health at Boston University, I try to use every semester to learn more about immense issues like birth outcome disparities or disparate impacts of social determinants of health on different populations. My coursework and regular engagement in the Racial Justice Talking Circles held on campus have ignited a passion to address these challenges, and I’ve begun to string together the theories and best practices to do so. However, after having completed my first semester I felt that my public health tool belt still lacked a critical driver for implementing programs that could address these complex challenges.

Recently, through my work in the Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network to Reduce Infant Mortality (Infant Mortality CoIIN) as part of my practice fellowship at NICHQ, I have begun to piece together that quality improvement (QI) strategies might be one of the most important tools to have handy in the field of maternal and child health (MCH). QI strategically connects the dots between evidence-based innovations and behavioral and social change frameworks that inform crucial innovations. To fully make this connection, there were three lessons that I had to learn:

1. Innovative changes that are developed with, not for, target communities will have a greater impact.

The true experts are those with lived experience and there must be a process for synthesizing logical ideas with creative solutions for unique challenges to advance and improve health outcomes. Improvement comes from critically and introspectively looking at practices to see how to create sustainable innovations for the communities that we serve.

As professionals dedicated to addressing disparities in health outcomes, we have a responsibility to include community members in identifying logical, creative and innovative thinking to create change. The complexities of MCH issues are illustrative of the full impact that the environment, social context and individual level factors have on community health. In seeking to address one facet of infant health we are suddenly faced with a host of individual behavior choices steeped in societal and political contexts that affect the overall health of our communities. The work being done by IM CoIIN state teams focused on smoking cessation illustrates how critical the supporting system changes are in helping women make behavioral changes. Innovations are successful when they take into consideration larger determinants of health such as a women’s access to supportive healthcare providers, local and state level policies that help women stay tobacco free, and public level of knowledge and attitudes toward smoking while pregnant.

2. We must be ready and willing to fail forward

Because there is no straightforward path to success, we need to be open and willing to fail forward. In developing small tests, data can be generated to understand whether an innovation adequately addresses a problem or yields the ideal outcome. For this reason, Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles empower practitioners who use them. If observations are different than what was expected, the PDSA cycle provides an opportunity to adapt, try again and innovate in real time.

This is not to say that evidence-based practices are not critical in public health work, but rather they should not be used as canned programs or be expected to translate seamlessly into every context and community. QI work takes evidence-based practices and encourages stakeholders to translate them for new contexts and communities. It is important to bear in mind that if an innovation worked perfectly upon implementation, there’d already be a stepwise guide on how to eradicate infant mortality. What we have to work with instead is a large and expansive evidence base and data that can be collected from current infant and maternal health initiatives. Working with these resources, we must enter brave spaces and challenge one another to put what we know into practice with the full intention of identifying ways to continuously improve rather than settling for the status quo.

3. Spreading an innovation takes data and a story

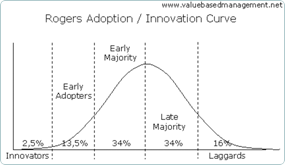

One of the core courses in my master’s program focused on the diffusion of innovation theory (right), where spreading change theoretically follows a bell curve shape with those most willing to change on one end and those most resistant to it on the other. Stories from the MCH community are incredibly powerful. Practitioners advocating for change can illuminate data with the stories from women and families whose lives are represented in numbers on spreadsheets. Stories compel change by communicating the problems and outlining necessary solutions.

Communication that seeks to compel those more resistant to change and evidence-based innovation should consider the factors that facilitate the spread of an innovation, such as the relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, testability and observability of the change. In using narratives to illustrate the advantages of a proposed evidence-based innovation, MCH practitioners can drive their communities towards improved health outcomes on issues that may have otherwise proven resistant to change.

It is no secret that the problems confronted by MCH professionals are both complex and intersectional. In the short time that I have left in both my fellowship and master’s program, I intend to approach barriers with an open mind and view each as an opportunity to stretch critical thinking skills and creativity while identifying relevant and sustainable innovations. We are not operating without our tool belts. It has become clear that every public health worker should have QI training and strategies ready to help develop and spread change for health issues that have deep ties to social frameworks. With QI strategies in hand we are able to collaborate to promote changes for problems that at first glance seem insurmountable, but with each adapted approach incrementally come into view as entirely possible.

Avery Desrosiers is a second year Masters Candidate at Boston University School of Public Health. She is currently working as the HRSA/MCHB Grant sponsored MCH Practice Fellow at NICHQ.