Eliminating the Consequences of Maternal Depression

Elaine DeaKyne was excited about her first pregnancy and, physically, she sailed through it without complications. Looking back, she recalls feeling anxiety during her third trimester, but she didn’t bring it up with her doctors because, as she says, “I didn’t know it was something I should talk about.” Her anxiety heightened after her daughter was born, but DeaKyne had no way of knowing that what she was experiencing was a symptom of maternal depression and could be identified and treated by professionals. No one offered her a mental health screening during her pregnancy or at her six-week follow-up check-up. No one discussed the risk and prevalence of maternal depression with her or empowered her to seek help.

DeaKyne was left alone with what became increasingly frightening thoughts and anxiety.

“When my daughter was six weeks old, I started to have these intrusive thoughts,” says DeaKyne. “There was one thought where I was walking my daughter in her stroller and just pushed her out into the street. Because of that thought, I stopped taking her out in strollers. Another time, I thought about driving over a bridge, getting out of the car, and jumping off. So, I started avoiding driving over bridges. I was so afraid of all these thoughts happening, so I just stayed home and isolated myself in this depressed state.”

DeaKyne’s experience is far from rare. Perinatal depression affects up to one in seven women in the United States. That translates to more than 180,000 mothers annually who suffer from an illness that affects their health and, as a result, the health of their children; an illness that is too often stigmatized and suffered through in silence.

Frightened by her intrusive thoughts, DeaKyne made an appointment with her obstetrician, and was immediately screened by a nurse when she arrived. At the last question of the screening, which asked if she thought she would ever hurt herself or her child, DeaKyne paused.

“I felt like the answer was, ‘I don’t know,’ but I wasn’t sure what to say,” DeaKyne. “The nurse was uncomfortable, and then she looked at me and said, ‘no, no you would never think or do that.’ She answered the question for me. In that moment, I realized I was going to leave this appointment without getting help, and I knew I really, really needed help. I just felt ashamed and afraid to say anything.”

Thankfully, DeaKyne did receive help. Her doctor also went through the screening with her and realized DeaKyne was struggling to answer that last question. Recognizing that something more serious was happening, her doctor connected DeaKyne with a therapist and she was immediately started on medication for depression and anxiety. It wasn’t the end of DeaKyne’s journey, but it was the first time someone recognized she was in need and stepped in and helped her. Now, six years since the birth of her first daughter, she is mom to two healthy daughters and serves as the Executive Director for Postpartum Support Charleston, a peer-support organization that helped her during her recovery.

***

DeaKyne’s story illustrates the critical need to do more to support the thousands of mothers and families affected by maternal depression. NICHQ’s recent webinar, Maternal Depression: Everyone Can Play a Role to Help Families Thrive, was dedicated to helping fill that need. During the webinar, DeaKyne shared her story alongside three other experts from the Brookings Institution, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Medical University of South Carolina. Together, their insights demonstrate maternal depression’s significant impact on mothers and families, and offer strategies health professionals can take to ensure that more mothers are screened and referred to support and resources.

Below, we share three high-level takeaways.

Lesson one: Maternal depression negatively impacts early childhood development and ultimately hinders future economic mobility

Maternal depression adversely affects the health of mothers, and in turn, the health of their children. This alone is significant, but it has additional concerning implications when considered within the context of economic mobility and cycles of poverty, explains Richard V. Reeves, PhD, Director of the Future of Middle Class Initiative and Co-Director of the Center on Children and Families at the Brookings Institution.

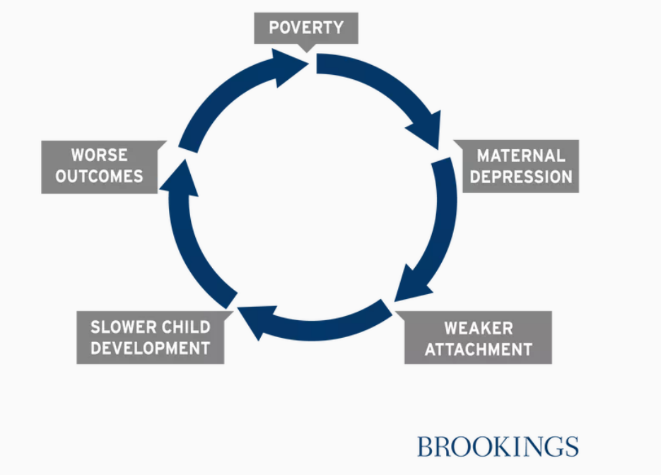

In what Reeves calls the “depression immobility cycle,” maternal depression is one piece within a larger cycle that feeds intergenerational economic inequalities. In sum: Poverty increases the risk of mental health problems, including maternal depression. In response, mothers experiencing maternal depression may have difficulty engaging in attachment forming behaviors and interactions. For example, because they feel disengaged, they may struggle to participate in “serve and return” interactions, where caregivers provide meaningful, appropriate responses to children’s gestures or sounds. These interactions shape brain architecture and without them, children’s developmental health suffers. Decades of early childhood science tells us that slower early childhood development affects children’s ability to succeed at school and develop meaningful relationships; simply put, a slower start results in worse outcomes. And consequently, children grow into adults who may struggle to find and maintain good employment, and eventually end up in poverty, facing the same risks of depression as their parents.

This cycle comes from a recent paper co-authored by Reeves, which examines the evidence for each stage of the cycle in detail. Ultimately, it points to the essential need to break this cycle at each and every stage and, says Reeves, “put mental health, especially maternal depression, at the center of the mobility debate.”

Lesson two: Leveraging preventive interventions for perinatal depression can help break the cycle

Early in 2019, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released a new recommendation related to maternal depression: all pregnant and postpartum individuals at an increased risk for developing perinatal depression should be referred to counseling interventions. This recommendation reflects convincing evidence that effective counseling interventions can help prevent depression before it even develops, says Vice-Chairperson Karina Davidson, PhD, MASc.

The Task Force found that when women engaged in effective counseling—specifically, either cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy—there was a 39-percent reduction in the likelihood of depression. Consider DeaKyne’s story: if she had received preventive counseling, she would have had to the tools to address her symptoms more immediately, or may never have experienced depression at all. Consider what that means for the nearly 200,000 mothers experiencing depression every year, and the thousands of mothers who never receive support and treatment.

While there is no accurate screening tool for assessing whether a person is at risk for depression, the Task Force did identify several factors that health professionals can look for. Specifically, says Davidson, health professionals should refer women to counseling if they have one or more of the following risk factors: a history of depression; current depressive symptoms (that do not reach a diagnostic threshold); socioeconomic risk factors such as low income or adolescent or single parenthood; recent intimate partner violence; and mental health-related factors, such as elevated anxiety symptoms. While there are no data on timing of referral, most of the interventions that were beneficial were initiated during the second trimester of pregnancy.

Along with preventive interventions, Davidson notes that the task force recommends screening all pregnant and postpartum women for maternal depression, and screening women of child-bearing age for intimate partner violence, which, if positive, signals the need for preventive interventions.

Lesson three: Strategies to increase access to treatment

Only 30 to 50 percent of women with mental illness during pregnancy and postpartum are diagnosed in a clinical setting, says Constance Guille, MD, Associate Professor and Director of the Women’s Reproductive Behavioral Health Program at the Medical University of South Carolina. Of that number, fewer than 20 percent are referred to treatment and fewer than five percent achieve remission from the disease.

Leveraging recommended screening tools for maternal depression, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), can help identify more mothers suffering from depression, says Guille, but we also need to put significant effort into addressing the barriers to treatment—namely a lack of access and stigma. Below, Guille offers four strategies she’s leveraged successfully in her own work:

NICHQ’s issue brief on maternal depression can help health professionals talk with families about the prevalence of maternal depression and its effects on early childhood development.